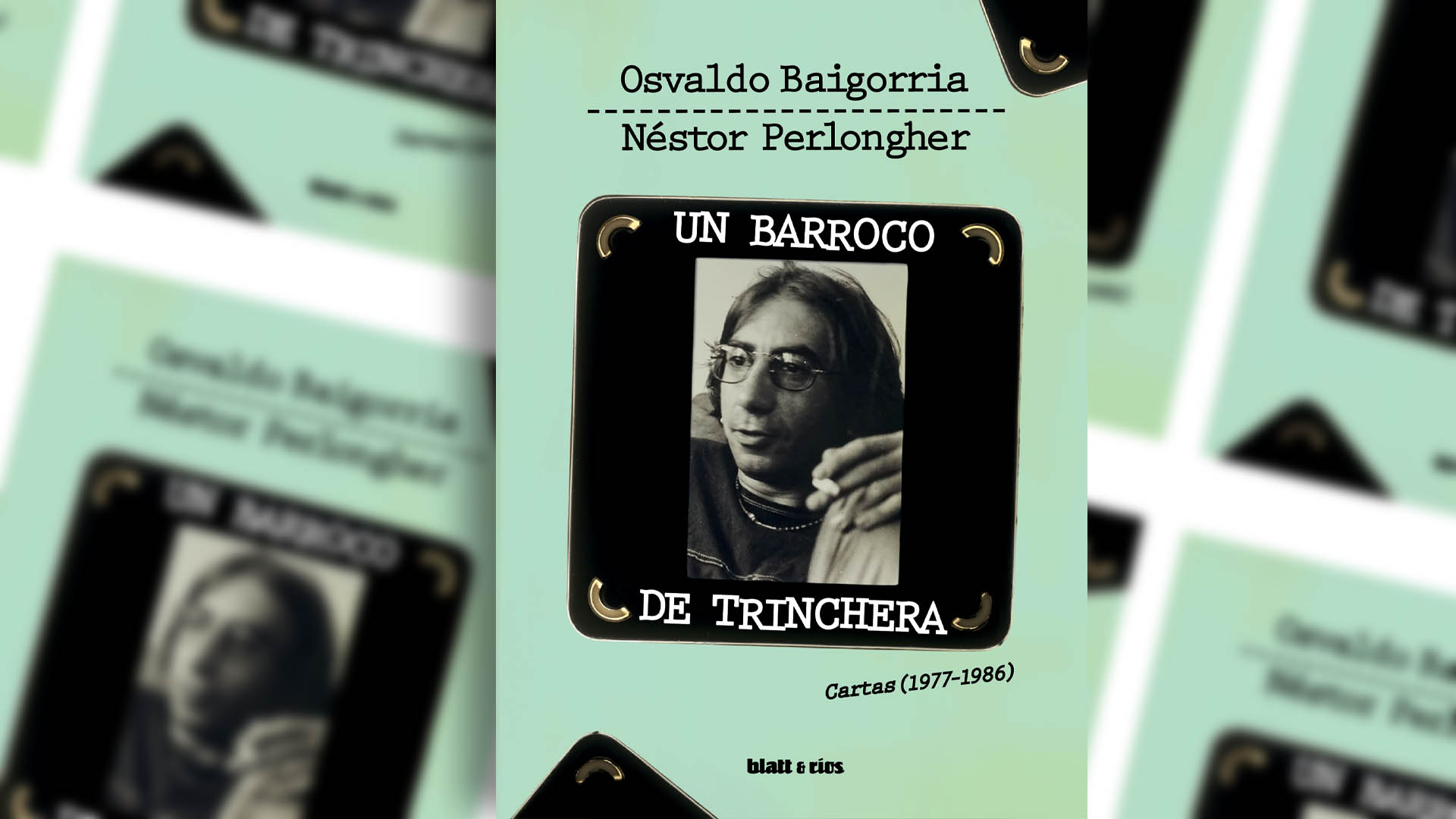

From exile in Brazil and throughout the last Argentine civil-military dictatorshipwriter, poet, journalist, sociologist and LGBT+ activist Nestor Perlongher exchanged correspondence with the writer, also Argentinian Osvaldo Baigorria. Twelve of these letters had been published by the Mansalva publishing house in 2006, but for almost two decades fourteen others had been waiting, forgotten, in trunks that traveled the world more than the average Argentine citizen.

“They first accumulated humidity in a cabin in the snowy woods of British Columbia in Canada. Then they flew in my carry-on from Vancouver to Buenos Aires. Then they were shipped in a packages by boat in Barcelona and by land in Madrid, in a final stage of residence until returning to their first land of origin or take-off”, writes Baigorria in the introduction to the new expanded edition of A baroque trench coat. Letters (1977-1986)edited by Blatt & Rios.

From his thoughts as an unpublished poet (at the time), to the subsequent success of his work and his activism, Perlongher, in mind-blowing paragraphs that hint at the dawn of one of the fundamental argentinian pens of the 80sturns his maps into battlefields where falklands warthe agony of the last military dictatorship, the struggle for equality of minoritieshis politico-sexual exile and a detailed description of return of democracy.

“Questions of relevance and belonging: can I say that they are mine? And do with them what I want? What would the living sender say to the idea of publishing them? Would you have wanted or imagined that they would leave intimacy to enter the public sphere? asks Baigorria in his introduction. The mixture of testimony of one of the most chaotic times in Argentina, added to its “strong literary charactermake these letters, nearly half a century after they were written, a bridge to get closer to this past in which lie the muddy roots of this present.

I want to present some specimens of a species that was already in danger of extinction in the 1980s. We did not yet know the word E-mail: this correspondence crossed the Pan-American highway by the south, the center and the north, with several letters and postcards that slept, got lost or were saved from the post offices of the Andes to the beaches of Rio, Bahía de San Salvador to San Francisco Bay, from the Argenta Mountains to the Argentinian Mud.

These letters are the only surviving ones of this journey, but they would have to travel still further before entering the realm of the limited future that the printing press promises. They first collected moisture from a cabin in the snowy woods of British Columbia, Canada. Then they flew in my carry-on from Vancouver to Buenos Aires. Then they were sent in parcels by boat to Barcelona and by land to Madrid, in a last stage of residence until the return to their first land of origin or take-off.

My answers won’t be here, which I imagine were hopelessly lost in an apartment in São Paulo inhabited by Perlongher in the eighties. Not all his letters either, but some of those he sent me between 1977 and 1986, sometimes signed n., others like Néstor and others like Rosa, alluding to Rose Luxemburg or Rosa L. de Grossman, the married name of the German Spartacist leader whom Perlongher used as a pseudonym in his early political writings.

“Delias de rimmel smeared, Etheles, roses in search of a Grossman lost in Luxembourg” he would say later, writing in his book son.

The course of these obituaries was that of my travels, pilgrimages, exiled and desexiled. I took them from one country to another, I cherished them without thinking that they would be publishable, just as the messages of old affections are preserved, by attachment, for stubborn resistance to oblivion; It was only in recent years, encouraged by friends to whom I read aloud some fragments, that I began to think that they had the right to take out of the drawer where the memories which did not arrive in time to encounter a hard drive bend and turn yellow.

For various reasons, I had doubts before publishing them. An important work of annotation seemed to me unavoidable so that its strong literary character could stand out in a documentary setting and for reading to find its way not only into what Perlongher describes as its “typographic entanglement” (extended hyphens, parentheses, arbitrary, excessive or non-existent punctuation, typos) but through the many references barely intelligible to those who knew the author closely.

Note that the recipient appears sometimes in the plural and sometimes in the singular. The name of “Osvaldo” or “Osw” in the first letters is added to that of “Milu” (with or without a capital letter, and sometimes composed as “miluos”) and to that of “their majesties” is followed by “your” , alluding to a certain ambivalence around the receiver. Milu is the name of my associate of those years, to whom Perlongher will address two letters in his name only during my absence due to a work trip (to plant trees ) and which it will also call “Shell of Miracles(due to a surprise phone call from San Francisco, an event that Néstor called “miraculous”), or simply “la Concha”.

Given that as a couple we had met Perlongher almost simultaneously, these letters to the two of us were well justified, at least at first. Over time, the plural ceased to be customary and the singular relationship he and I had had when we first met began to prevail.

This first agreement with two people who are one and then they end up dividing and isolating is the expression of a step-by-step process: Néstor (Rosa) first writes to us and then he writes to me.

Relevance and ownership issues: can I say they’re mine And do with them what I want? What would the living sender say to the idea of publishing them? Would you have wanted or imagined that they would leave the intimate to enter the public sphere? Would you have written them differently then, corrected a bit, with some editing more or less, a word crossed out, repressed, blurred? I feel that, in some way, I have to symbolize my request for permission to a memory.

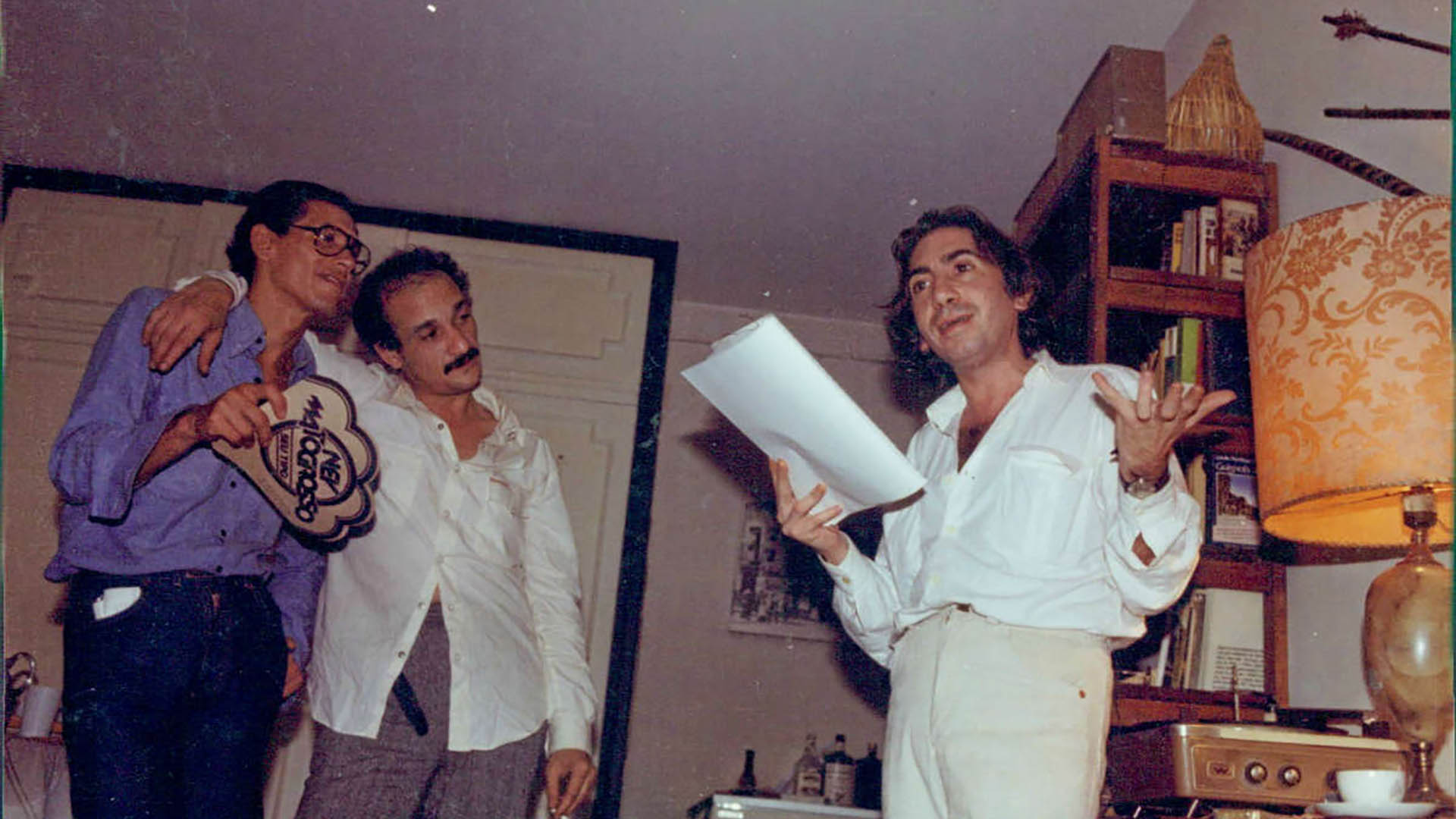

I said I remember and I know I’m lying. A first image emerges: the day I met him, in 1972. He was twenty-one years old and had mid-length hair. In a stately home in Flores, in front of fifty people gathered to found Sexual Policy Study and Practice Groupuncrosses her legs dressed in brown corduroy pants with bell bottom boots, settles on her platform shoes and introduces herself: “I am a member of the Homosexual Liberation Front of Argentina”. You can’t say she was pretty, the Rose. Rather short, with a round face, with eyes with intense black gaze on a nose that should not be missed. But he knew how to fight (and make himself visible).

Dear Miluos (Milusz)?

In such a special state as this, I started a letter to You) that in the midst of the disorder that characterizes me, I cannot find. It’s too bad, and if I find it and something she says seems shippable to me, I’ll attach it.

Accompanied by a detailed explanation of this delay, which is due to the futile, fortuitous and banal fact of the holidays of the people to whom you were kind enough to send it. I don’t quite understand this passage, other than a distant wish that my communication with your other national correspondents will intensify, in which case success has crowned such distant efforts, in a somewhat delayed way.

Your location in a very remote place (oh restful life, etc.) paradoxically coincides with my movement towards these absurd suburb of Baires that Eva and I (who accompanies me in this third home) (Eva and I) have decided to rename the Gallicism of The Painting, Party of the Massacreanticipating the imminent declaration of Marinos del Fournier as the capital of the CAR.

Further this malambo doesn’t stop being urban, with all the disadvantages of the city and none of its advantages. “Mad cows that you accuse/cultivate for no reason…” (Paraphrase).

It is extremely difficult for me to enter into this national solemnity whose spirit, I fear, will end up tinting this blue.

I appreciated the fruit of Milu’s special friendships with God, although the fear that he would listen to us censored news about my status. In any case, your mail arrived safely thanks to intelligent management before the mail. However, you are soon writing to me at my brand new address (without much burnt aroma yet) which is: NP Crovara 2968 – dept. 1 1766 – Tablada –

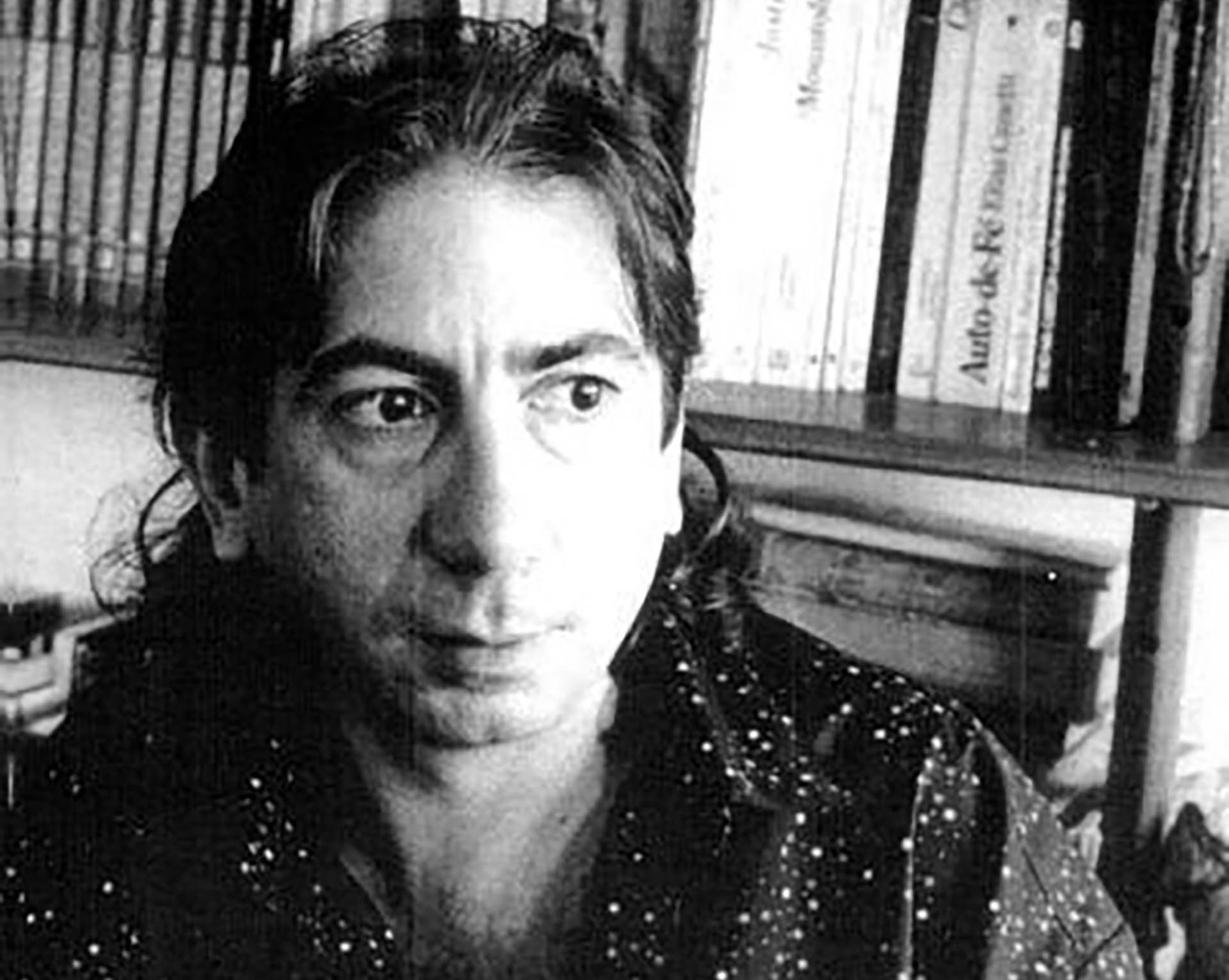

♦ He was born in Avellaneda, Argentina in 1949, and died in São Paulo, Brazil in 1992.

♦ He was a poet, writer, journalist, sociologist, LGBT+ activist and one of the founders and main referent of the Argentine Homosexual Liberation Front.

♦ Wrote books like more common prose, The ghost of AIDS, son, Rubber And I licked.

♦ Born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1948.

♦ He is a writer, journalist and teacher.

♦ Wrote books like Take her, my friend, for the good of the three of us., You would run away from an infidel, indianada And tiger bark.

Continue reading:

“Amateur introvert. Pop culture trailblazer. Incurable bacon aficionado.”

:quality(85)//cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/REIJKJOUWZAUJMUDPD3O2XQIYQ.jpg)