In Japan, it is not possible to leave the car on the street; since 2014, you must prove that you have a garage, owned or rented, to buy a car. Too radical? Climate, social, economic and environmental challenges are forcing us to rethink our streets, squares and mobility networks and these changes are forcing us to give up, but in return we will live better. Lo explains the Canadian investigator Charles Montgomery (Vancouver, 1968) in ‘Ciudad feliz’ (Capitán Swing), a book that analyzes as a designer urban green and intelligent, with menos asphalt, menos vehicles y más árboles y fuentes exponentially increase the quality of life.

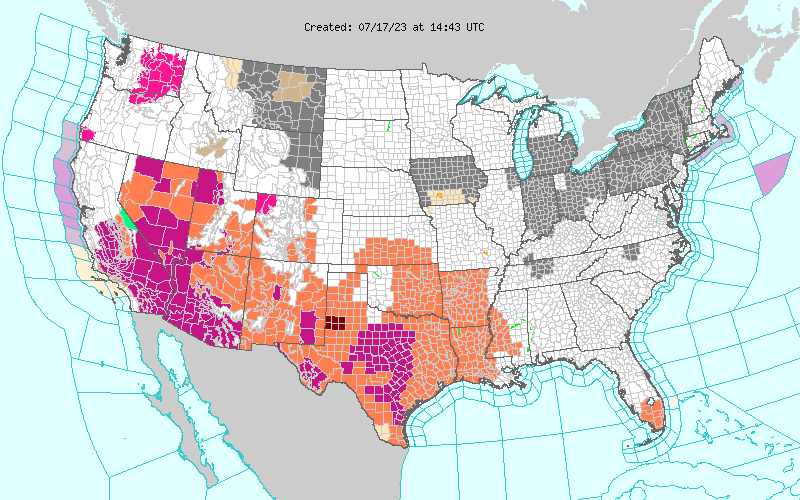

This trial could not come at a more opportune time: just after the hottest April in Spain in sixty years and with the center of Murcia buoyed by a mobility plan that points timidly towards a more sustainable future without however enter into necessary modifications, despite which it raised protests in neighborhood groups and traders.

In which city do we want to live? In a city devoted to the car or in certain streets where you can walk and breathe, isn’t this a risky activity? Where to walk in the shade of trees or have to cross large deserted squares under a scorching sun?

Dominant urbanism ‘makes us fatter and sicker, steals time and makes life more expensive’

In ‘Happy City’, translated by Blanca Gago, there are some clues. For example, in Paris, a large city that has undergone a major transformation in recent years: underground public transport has been reinforced, hundreds of kilometers of cycle paths have been built and urban beaches have been developed. The capital of France is even more beautiful now, and also more welcoming to tourists and Parisians.

health hazard

“Our cities have never used so much land, energy and resources. Never before has living in a city required converting so much primary sludge into a gas capable of heating the atmosphere. Despite everything we invested in the sparse city, it failed to maximize health and happiness. It’s a system full of inherent dangers: it makes us fatter, sicker, and more likely to die young. It makes life more expensive than it is. He steals our time. It is difficult for us to keep in touch with our friends, our family, our neighbours. It makes us vulnerable to economic crises and the inevitable rise in energy prices that the future implies. As a system, it began to jeopardize the health of the planet and the well-being of future generations,” writes Charles Montgomery.

The happy city is not a homogeneous model. The book begins with the bicycle revolution promoted by Mayor Gustavo Peñalosa in Bogotá in 1997. He knew he could not increase the wealth of his neighbors or face major economic and social changes, but he chose to transform the capital of Colombia to make it more human.

The extensive network of bicycle paths, parks and pedestrian plazas, libraries, accessible schools and daycare centers, as well as the banning of private vehicles in the center have increased the well-being of Bogotanos.

These lessons, which in countries like the Netherlands and Denmark did not need to be imposed – each Dutchman pedals 2,000 km a year – are also applied in southern Europe – Barcelona, Vitoria, Valencia , Seville…–, with the new paradigm that cities are no longer designed for existing traffic, but for the traffic they wish to have.

“Devoted organizer. Incurable thinker. Explorer. Tv junkie. Travel buff. Troublemaker.”