It is proposed here to update the work of the Canadian political scientist Pierre Ostiguy: Péronisme et anti-Péronisme: socio-cultural bases of political identity in Argentina, text published in 1997.

Invariant. The reason for the persistence of this trabajo is that, so well matched the gran mayoría of los political actors, hay an invariant núcleo in the argentine política that permanent and that is related with the sociopolitical categories and su dynamica, tal como lo plantó Ostiguy 25 years ago. By this time, Carlos Menem had almost total control of Argentine politics, had achieved constitutional reform, and was enjoying his second term without major shocks, save for corruption complaints, and a lukewarm opposition that was emerging. from its own ranks with the breaking of the deputies led by Carlos Chacho Álvarez.

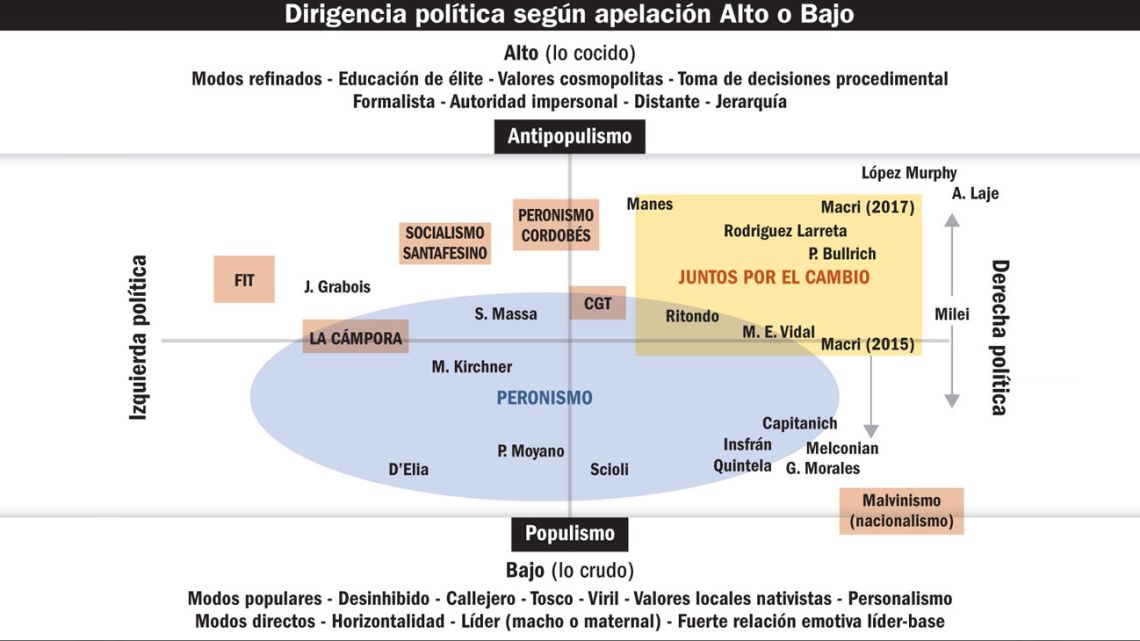

Going to the theoretical core of the Canadian to analyze Argentine politics, the author explains that it does not reach the traditional right-left axis. This axis, always relevant, must be crossed by socio-political identity. The Up-Down axis is a cartography of two antagonistic socio-cultural formations, not only because of the positions of the agents on the economic map, but also because they imply completely different practices, values and readings of reality. The persistence of this axis could constitute one of the rare bridges between the 20th century and the current one.

How Argentines perceive their quality of life

Who are we? Ostiguy’s classification maintains the freshness of the researcher who can look at Argentine reality without being emotionally and ideologically involved, so he “dares” to generate political categories and explain them precisely. The High and Low socio-cultural identities are not necessarily linked to the economic level of the agents (although they are associated). For example, many affluent university students may adhere to the “low” even in their habits and values. On the contrary, a good part of the middle layers, always enigmatic, tend to adhere to the valorizations of the Top, although they are sometimes foreign to its economic reality.

For this reason, the low and high spaces are modes of recognition marked by the distinction between the (culturally) popular and the cultural elite (the well-educated), respectively. These logics in Argentina have become politicized, they have become marks of political identities which, from the emergence of Peronism, are linked together as modes of appeal to the political sphere. To be clear, it doesn’t matter if the politician more or less shares this socio-cultural position (it doesn’t work that way), but rather if he shares a certain communicational code that allows political representation.

Objections. The code referred to is complex, multidimensional and changing, but it is linked to a series of clearly recognizable positions. For example, high space is generally associated with “good manners”, admittedly formal, with cosmopolitan expectations, admirer of modernity, institutional values, sharing of powers, impersonal forms of authority, appreciation more marked hierarchies, meritocracy as a social mobilizer, etc. On the other hand, the low, popular space assumes a curious term (controversial and somewhat old) that Ostiguy uses: it is an adequate “periphery” in the sense that the members of this space rarely access the high spheres of politics. . Then, the Bajo is associated with localism (as opposed to cosmopolitanism) and that it can acquire a nationalist character or its “Malvinas” version. If the preference for impersonal (anti-populist) leadership was characteristic of the Alto, in the Bajo personal authority is valued, the male or maternal leader (the author describes him as “affectionate” thinking of Eva Perón). This strong leadership is well recognizable and among the most dispossessed sectors, it is seen as their only real possibility of social inclusion. On the other hand, in rational authority in Weberian terms, they do not find their space of representation at the bottom, which explains the general misunderstanding between those who argue, for example, in the priority of republican power-sharing and for those which it does not mean more a formality that hides the forces that try to limit the leader.

Objective: Pink House

Plans. This means that one can see in the interpretation of the chart that today’s Argentina has moved to the right, where much of its leadership lives. Cristina Kirchner has two characteristics that no other political leader shares, that her symbolic appeal is aimed primarily at the Bajo, despite capturing certain sectors of the middle-class intelligentsia, but she also has the versatility to move in the right-left horizontal axis, being able to appeal to both nationalist values and those of the anti-capitalist left.

Then only one leader of the opposition was able to move on the vertical axis and it was Mauricio Macri who challenged the low base of the football call, however, as of 2017 Macri embraces the high call and prepares its electoral defeat of 2019. The other two leaders within JxC who have some skills to seduce the Bass are María Eugenia Vidal and Patricia Bullrich, the first for not belonging to the founding elite of the PRO and the second for its past Peronist, his verbal ways and to take security as a discursive axis. But as a whole, JxC belongs and appeals to high values. Perhaps the best exponent of being located in the upper right corner is Ricardo López Murphy, but paradoxically another economist with whom he shares positions, Carlos Melconián, appeals to the Bottom, a rare bird among economists.

Then, the case that tends to be an exception to the rule is Javier Milei, his ideological baggage is on the extreme right but his radius of action is wide, which explains his popularity. As can be seen on the political left, the FIT or Santa Fe Socialism appears, but the call to the Top limits them electorally. Finally, a curious situation is that of Cordovan Peronism which works with the logic of territorial encapsulation (as happens with the Popular Movement of Neuquén), and which fails to connect with the Bajo.

The model proposed by Ostiguy can probably be corrected or updated, however, it continues to generate clues for Argentine sociopolitical understanding.

* Sociologist (@cfdeangelis)

You might also like

“Amateur introvert. Pop culture trailblazer. Incurable bacon aficionado.”